Data-driven, proactive prevention. Are we finally ready for population health management?

As we navigate the complexity of modern healthcare, it is clear that preventative, data-led approaches can help solve some of the NHS’ major challenges. But ‘are we finally ready for population health management?’ asks Health Navigator CEO, Simon Swift.

I am sure every generation of health and care leaders think they face unprecedented challenges. I don’t think it is an error to say the current NHS leadership feels this, and with some justification. Urgent and emergency care services are under immense pressure, planned care waiting lists remain very close to the 2023 high of 7.7 million, while persistent health inequalities threaten the foundations of the UK’s universal healthcare model.

We must ask ourselves a crucial question: what, if any, proven approaches are there to deliver better outcomes for patients while ensuring the long-term sustainability of our health systems?

I firmly believe that the answer lies in harnessing the power of data. This data-driven approach takes different shapes at different points across the system. For example, optimising system design and service scale and location at the macro level, while at the micro level, there are cumulative marginal gains to be made through ‘command centre’ type solutions to operational management, optimising efficiency and safety for people in A&E or waiting for planned care. These are impactful uses, but not sufficient.

Another use of data is to enable a shift from reactive to proactive care models. Logically it is attractive; we stop people becoming acutely unwell, which is good for them. If they don’t become acutely unwell, they don’t need urgent and emergency care, reducing demand at the front door. This (in the UK system) means we can allocate resources to focus on other things, and there is plenty to do. If we are going to be responsible custodians of health services, this transition is not just desirable; it’s imperative.

The case for change: A closer look at the crisis

Waiting times for emergency care have reached historic highs, which is a miserable experience for patients, an awful work environment for staff facing intolerable moral hazard and probably dangerous.1 Bed occupancy rates in many hospitals mean managers are in constant firefighting mode, with waits backing up into A&E and elective cancellations routine, without a bed to admit a cold patient into.

Though this pressure on hospitals is universal, emergency department attendance rates are more than twice as high for those living in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived, demonstrating the deep-rooted inequalities in our health system and society. The inverse care law is alive and well.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues, creating a backlog of need that will take years to address. Moreover, an ageing population and the rising prevalence of chronic conditions are adding to the complexity of healthcare delivery. These challenges are not just statistics; they represent real people experiencing pain, anxiety, and diminished quality of life for many.

A data-driven approach to prevention

I believe we must use preventative, data-led, approaches to address these challenges, finally taking a step away from sole focus on the traditional reactive model. The evidence base is growing that the logically attractive proactive, preventative approach, leveraging the data at our disposal, actually works.

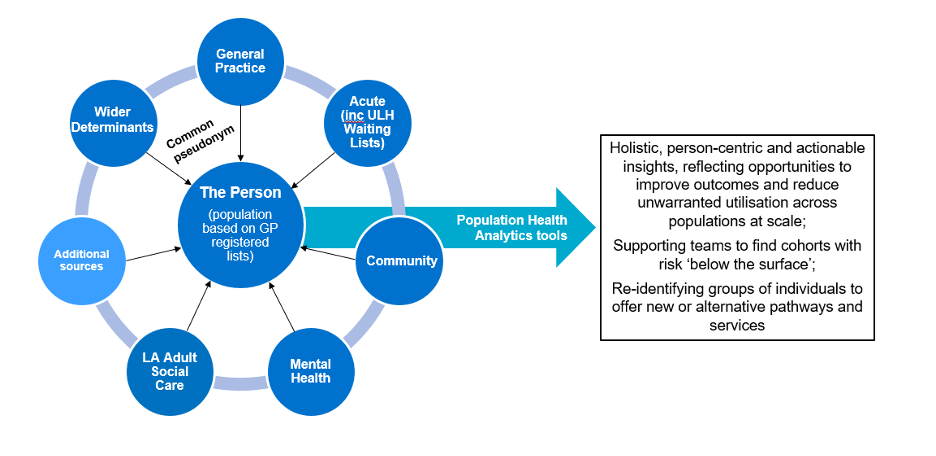

By harnessing this data (how this works is a sexy thing to some – advanced analytics and machine learning algorithms), we can identify patients at high-risk of unplanned care needs months in advance. This foresight allows us to intervene early, providing personalised support that empowers patients: precision population health management (PHM). The potential of this approach is enormous, offering a way to improve people’s health and so reduce pressure on acute services in the short-term and planned care in the longer term.

At HN, we’ve seen first-hand the transformative impact of this precision PHM approach. Our Proactive solution has demonstrated significant reductions in emergency admissions and A&E attendances.

Empowering patients and supporting healthcare systems

With advice from the Nuffield Trust and with the support of several NHS trusts, HN conducted a randomised controlled trial.2 It meticulously tracked up to 2,000 patient outcomes across multiple trial sites. We demonstrated a 36 per cent reduction in A&E attendances for patients supported by health coaching, which is in line with other studies. This isn’t just about numbers; it’s about people avoiding traumatic emergency visits and receiving care in more appropriate, less stressful settings.

The benefits of proactive, data-driven care extend far beyond reducing hospital admissions. We saw improvements in mortality rates, Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROM’s), patient activation, and quality of life.

These outcomes are transformative on multiple levels. For patients, it means taking control of their health, understanding their conditions better, and enjoying an improved quality of life. For healthcare systems, it translates into reduced pressure on acute services, better resource allocation, and improved overall efficiency.

This approach helps to address health inequalities. By identifying at-risk individuals early, regardless of their socioeconomic background, we can provide targeted interventions that prevent health issues from escalating. This is particularly crucial in areas of high deprivation, where health outcomes have traditionally lagged. For those close to this type of risk modelling it will be no surprise that deprivation (income and health) is a significant risk factor.

The role of technology

As we navigate the complexity of modern healthcare, it’s clear that innovation and technology will play a crucial role. However, it’s essential to understand that technology is not a panacea. The true power lies in how we apply these tools to reimagine healthcare delivery. Those who have worked in this arena for any length of time know that implementing a technology rarely delivers benefit alone, and is often problematic and unhelpful. Carefully designing the change in process, behaviour, decision making etc. that the technology enables is the key to delivering value.

While the potential of data-driven, proactive healthcare is material, we must acknowledge the challenges in implementing the approaches. Data privacy and security are serious concerns that need to be addressed rigorously. We must ensure that as we leverage patient data for better care, we do so in a way that respects individual privacy and complies with all relevant regulations. However, the current red tape-bound and bluntly obstructive approach to information governance in the NHS needs improving if we are to derive value at a meaningful scale and pace.

Looking to the future

The opportunities are tantalising. By embracing data-driven insights and personalised interventions, we can create a more proactive, efficient, and equitable healthcare system that actively helps people live healthier for longer. This approach not only addresses immediate pressures but also lays the foundation for a more sustainable future.

The change from sickness to health care will require collaboration across all sectors of health and care – from policymakers and healthcare providers to technology companies and, most importantly, patients themselves. We need to encourage innovation, where new ideas can be tested and scaled rapidly.

At HN, we’re committed to being at the forefront of this transformation. Our work in AI-guided clinical coaching is just the beginning. We envision a future where patients receive personalised, proactive care that keeps them healthy and out of the hospital.

References

1 Jones S, Moulton C, Swift S, et al. Association between delays to patient admission from the emergency department and all-cause 30-day mortality. Emergency Medicine Journal 2022;39:168-173.

2 Bull LM, Arendarczyk B, Reis S, et al. Impact on all-cause mortality of a case prediction and prevention intervention designed to reduce secondary care utilisation: findings from a randomised controlled trial

Emergency Medicine Journal 2024;41:51-59.