Damaging NHS disputes hindering progress on productivity, finds survey

Trusts making progress on NHS targets and taking steps to boost productivity but concern mounting about staff morale and burnout as operational pressures take their toll.

Ongoing industrial action presents a major operational and financial challenge for NHS trusts, and is hindering all trusts’ ability to recover productivity, according to a new survey carried out NHS Providers. It highlights the scale of the task ahead for the NHS, as it simultaneously grapples with increasing numbers of patients with complex conditions staying in hospital for longer, emergency care pressures and limited bed capacity, exacerbated by the crisis-hit social care sector.

Trusts across hospital, community, mental health and ambulance services have made significant early progress towards meeting care backlogs for urgent and emergency care, cancer tests, long waits and diagnostic services as they strive to deliver better outcomes for patients, say NHS Providers.

They have introduced a range of measures to boost productivity in the NHS – delivering more care with existing resources – including targeted initiatives to improve staff health, wellbeing and retention alongside efforts to help discharge patients faster and adapting their buildings to treat more patients.

But trusts are now warning that eight consecutive months of industrial action across the NHS are taking their toll on efforts to cut waiting lists, with more than 651,000 routine procedures and appointments rescheduled so far and many tens of thousands more likely to be delayed as the health service faces back-to-back walkouts by junior doctors, consultants and radiographers in the coming days.

“Increasingly hard to improve productivity”

The new survey by NHS Providers, Stretched to the limit: tackling the NHS productivity challenge, outlines the scale and complexity of the challenge ahead, particularly as trust leaders count the cost of industrial action given the disruption to planned care, and increasing costs due to agency spend and the impact of consultant rate cards.

The Chief Executive of NHS Providers, Sir Julian Hartley, said: “Leaders and staff are working flat-out to cut waiting lists and to see patients as quickly as possible in the face of major obstacles.

“With waiting lists at a record high, trusts are keenly aware of the need to carry out more operations, treatments and scans. They are doing everything they can to see more patients more quickly and to deliver better quality care, including introducing virtual wards and new initiatives to speed up hospital discharge and offer more care at home.

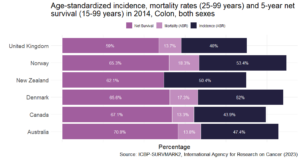

“However, it is increasingly hard to improve productivity because of staff burnout, high turnover, vacancies, a rising number of patients with more complex conditions, stretched community and social care capacity, and fewer hospital beds per person than comparable countries.

Trusts are also warning that it will be very difficult to deliver the government’s overall demands in terms of performance while delivering unprecedented efficiencies, seeking to protect quality of care for patients.

The survey finds that:

- Almost nine in ten (89 per cent) trust leaders said the scale of the efficiency task is more challenging than it was last year.

- Almost three in four (73 per cent) did not think they had access to sufficient capital funding over 2023/24 to cover the costs of vital repairs to buildings and equipment.

- Nearly two thirds (61 per cent) were not confident that they and their system partners would hit targets to reduce long waits for mental health care.

- Fewer than half (43 per cent) expect to meet an interim recovery target of 76 per cent of A&E attendances to be seen within four hours during 2023/24.

The findings reveal widespread worry among trusts about having to deliver more for less as budgets, staff and resources are stretched to the limit, leaving trust leaders facing increasingly difficult dilemmas about how to sustain services in the future.

Despite an overall increase in workforce numbers and the welcome promise of more staff in the future through the new long-term workforce plan, rising concerns about staff morale and burnout also continue to play heavily on trust leaders’ minds. They are contending with 112,000 vacancies across the health service in England with staffing numbers and skill mix failing to keep pace with growing and changing demand.

This is piling on the pressure, with trust leaders identifying discharge delays, relentless demand on emergency care, a lack of investment in social care and a dependency on agency staff as the biggest barriers to returning to pre-pandemic levels of productivity.

They are clear that capital investment in the NHS estate is also key to boosting productivity. This would allow trusts to expand bed capacity and community provision, deliver digital transformation, bear down on care backlogs and eliminate the persistent inefficiencies created by creaking buildings and equipment.

But with the NHS capital maintenance backlog now exceeding £10bn, and only a handful of trusts benefitting from much-needed investment through the New Hospital Programme, a great many more need urgent major capital investment to overhaul their ageing estates to achieve better – and safer – outcomes for patients.

Sir Julian Harley added: “Industrial action also poses a significant financial risk to trusts, given the disruption to planned care, and increasing costs due to agency spend and the impact of consultant rate cards.

“The new long-term workforce plan with its focus on recruitment, training and retention could finally put the NHS workforce on a sustainable footing if commitments are made to keep it updated and funded. But the benefits of that plan can only be reaped with a wider focus on productivity and its enablers, many of which we explore in this report, such as investment in management capacity and capital.

“If we are to ramp up productivity across the NHS, we need a step change in capital investment to provide more beds, more community care, a digital revolution, a safe and comfortable therapeutic environment, and appropriate support for social care.”