Elective backlog and care priorities: a call for localised solutions

Edge Health’s George Batchelor and Lucia De Santis explain the need to develop localised solutions to drive the NHS’s elective care recovery.

March 2020 marked an unprecedented change in the NHS and healthcare provision. As resources were diverted to the pandemic response, virtually all elective activity ceased, and the healthcare system transformed into a huge acute response machinery. We knew this would not be a sacrifice without consequences, but it was worthy of the stakes at play – millions of lives affected by COVID-19.

Fast-forward three years: the pandemic is now over for many people, but its impact on the NHS remains. This impact goes beyond the ever-growing elective backlog to include a fundamental shift in how care is provided, as well as a host of top-down targets that place increasing challenges on care providers.

The state of the elective recovery

Many will be familiar with the dire state of waiting lists for consultant-led elective care that topped 7.2m in October 2022 – a 64 per cent increase from March 2020 and with a median waiting time of 102 days.

Amid efforts to tackle the backlog, the recovery strategy has pushed for “doing more” with an ever-increasing range of performance measures to drive increased throughput and avoid adverse incentives, including: achieving zero 65-week waits by March 2024, increasing completed pathways by 110 per cent, increasing valued activity by 104 per cent, performing all diagnostic tests within 6 weeks, and several more.

Competing targets can be confusing to navigate and add pressures to already stretched systems, but they also fail to account for novel care challenges and regional variation. Working closely with trusts and ICBs, Edge Health has encountered, again and again, a stark increase in patient complexity since the pandemic and the consequences of a depleted, exhausted workforce that don’t show up in figures and targets.

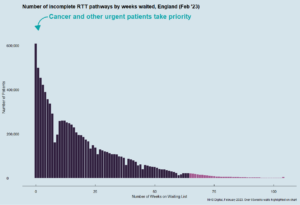

To add to this, Covid has also prompted a greater focus on prioritisation and clinical urgency in allocating care, as opposed to a first come, first served system, which poses added challenges in correctly allocating services when some patients have been on a waiting list for more than two years.

How targets fuel a new hierarchy of care: emergencies, long-waiters, then everyone else

Despite the impressive efforts and successes of restoring elective activity after the pandemic, as well as the rise of innovative ways to provide care and promote collaboration among providers, we are still far from having room to breathe. In this context of significant mismatch between demand and capacity, the limitations of national targets that would encourage efficient management in a balanced system are laid bare.

A pertinent example of this is elective waiting lists, which have been the object of various targets to reduce long waits. The good intentions behind these targets are undeniable; no one should be made to wait for care for more than a year. In a system where demand is matched with capacity, such long waits should never be an issue. In principle, a sudden surge in capacity directed at these long waiters might be enough – at least for some trusts – to clear them. However, this is problematic for two key reasons: it fails to account for clinical urgency and the resources that must be reserved for the sickest patients, and it directs disproportionate energy to 2 per cent of the waiting list.

Previous experience shows that initiatives to address targets are incredibly energy-consuming for trusts. They may also fail to gain buy-in when they don’t match local clinical priorities. What we have seen at large trusts is that the backlog of elective diagnostics does not stand a chance in front of the volume of emergency and two-week-wait cancer referrals. As patients approach waiting targets, however, they are pushed to the front of the queue to avoid missing them. This is not solving the backlog issue – it merely adds another pressure point.

Perhaps more throughput-focused national targets, such as setting a maximum number of waiting-list per head of population, would be more effective while allowing trusts to decide how to manage their own waiting lists.

ICBs create an opportunity to focus on local priorities

If there is one thing that the pandemic has demonstrated about the NHS, it is that when empowered, trusts and local systems are pioneers of innovation and can rise to unprecedented challenges. From the London Ambulance Service, which partnered with the London Fire Brigade to deal with rising ambulance demand, to the Royal Surrey NHS Foundation Trust that partnered with a local private hospital to provide excellent palliative care despite the pandemic (NHS Providers, 2020), the pandemic bore witness to numerous examples of unparalleled collaboration and innovation.

There is an inevitability about some targets in that they reflect national priorities and are a way of tracking progress and holding systems to account. There is some evidence to suggest they motivate change and can be a catalyst for improvement. But the flipside is that blanket targets don’t take into account local need and they penalise providers that are otherwise making huge progress on elective recovery. They’re also not particularly good at motivating staff in a positive way—health and care professionals understand that targets are organisationally important, but they’re not always aligned with what professionals and patients think is important. If ICBs are to be held accountable for delivering on targets, it only seems fair that they should have a say in what the targets might be and it can be expected that priorities might change from one locality to another.

This should not be seen as a limitation, but as an opportunity. We think ICBs are the key for a more nuanced approach to designing and setting priorities that might catch two (or more!) birds with one stone: managing the elective backlog and addressing local need with highly relevant targets.

ICBs could set their own targets, that are in line with national priorities but refined to fit local circumstances. Local systems could engage their workforce and patient voices in agreeing what these look like. This approach still creates accountability and sets a direction for change (the point of targets) but also gets buy-in from the teams charged with meeting the targets—targets that reflect their priorities and what they see in their own practice.

It doesn’t have to mean a free-for-all or ducking difficult problems. National bodies can still ensure local systems are ambitious, hold them to account, and provide support and guidance to deliver change. Programmes such as GIRFT do this very successfully. Instead, what we propose would allow local systems to have more freedom to invest in novel care strategies to tackle their unique challenges. Importantly, it could be a mechanism to engage with, value and retain the workforce.

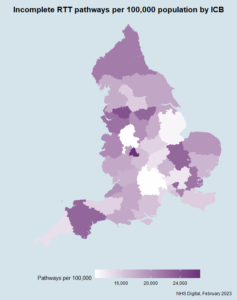

Of course, the counter is that differences will emerge across localities. But the truth is that this is the current reality, demonstrated by the charts above. And those differences would likely start to narrow if – and this is critical – ICBs are given time to flourish, work to meet local priorities and learn from one another.

About the authors

George Bachelor is Co-Founder and Director of Edge Health s

Lucia De Santis is a qualified medical doctor and Analyst at Edge Health, providing

For more information about Edge Health, please visit www.edgehealth.co.uk.