Non-emergency transport is crucial for winter resilience

Seasonal pressures and existing backlogs look set to increase demand for non-emergency transport this winter. Writing for ICJ, ERS Medical’s Chief Executive Andrew Pooley, and Quality and Governance Director Simon Smith, outline why they are pushing hard for winter transport resilience.

The NHS was already experiencing significant pressures, even before this winter’s challenges. Although a smaller component of the NHS, non-emergency transport services (NEPTS), which provide transportation for patients with non-urgent conditions but who would struggle to travel independently, play a pivotal role in maintaining smooth patient flow.

Last year, ERS Medical launched a campaign to raise awareness of non-emergency transport. The aim of this, in part, is to emphasise the importance of non-emergency transport and more importantly, to encourage the earlier booking of contingency winter patient transport shifts to support hospitals with patient discharge and alleviate some of the anticipated winter challenges.

Easing system pressure

Delays to patient discharge cause significant patient flow issues, and these are well documented. News headlines often focus on bottlenecks and delays via front door admissions, such as A&E, and the significant pressures being faced by emergency departments.

However, if beds are not available in hospital wards where patients can be treated after assessment in A&E, there is less capacity for newer patients to be admitted. The traffic jam at the exit route now becomes a problem at the entry points for patients, as well as preventing ambulances from returning to the community, increasing already dangerously long ambulance response times.

One of the main reasons for the patient flow crisis is the availability of social care. There is a direct correlation between the absence of an ongoing care package and higher rates of readmission. Further, discharging patients too early without any ongoing care and proper safeguards in place will often mean the patient is readmitted sooner or later. Poor discharge protocols can also lead to an increase in complaints and reputational damage for hospitals. It is no surprise then that discharge coordinators and healthcare staff have such a tough balancing act to manage, in addition to their workload challenges.

The role of transport

Transport can play a huge role in addressing the discharge backlog, and booking transport early is vital. This may sound simple enough, but transport is an often-overlooked aspect of the discharge process. When patients are ‘made ready’ for discharge, this is often the first point at which transport is considered. However, booking transport in advance, preferably the day or so before the patient will be ready to leave, is usually more efficient. While it is difficult to be a hundred per cent certain that a patient will be ready for discharge on a particular day, clinicians often have a good indication of when discharge might be feasible and appropriate.

To this end, planning and communication are essential. Planning the transport in advance, booking it and then communicating with the provider if the plans change for any reason are crucial elements in the efficient discharge of patients. This ensures there are enough resources available in the system for trusts and integrated care systems to keep the patient flow running smoothly.

One solution that is showing promise is to appoint specialist patient transport liaison officers (PTLOs) in hospitals. This “human” point of contact is a specially trained individual who can assess transport needs and then recommend the best approach on a case-by-case basis, often communicating with patients, hospital staff and families to keep everyone informed.

Lessons from previous spikes in demand

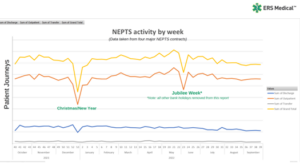

Contrary to conventional wisdom, one of the key insights from looking at our data (as illustrated below) is that spikes in winter demand often arise, not because of increased activity levels, but because of changes in booking behaviour, patient mobility, an increase in aborted journeys, and the subsequent need for more resources to accommodate these changes.

Let’s take a hypothetical fleet of 10 vehicles servicing a local acute hospital. With the “normal” commissioned pre-planned booking behaviour and mobility mix, the activity matches resource and there are no service issues. Add in just one complex journey – for example, an obese patient that requires an additional crew to assess the property and support the journey – very quickly, that can reduce 10 per cent of available resource for more than half a day.

Add in multiple issues – for example, bookings made at the last minute, or with incorrect mobility requirements, or patients’ drugs not being ready at the pickup time – and it is possible to see how demand outstrips built-in spare capacity and pressures build in the system. Integrated care boards (ICBs) should act with caution when being presented with supposedly easy fixes. The Uber model does not work with a regulated service that relies on trained staff and specialist equipment, and simply drawing on resources from outside the contract often fails because other services will also be under pressure, as they rarely hold spare capacity. The simple answer is to plan well in advance – it takes time to mobilise a fully compliant NEPTS ambulance crew, communicate with all stakeholders and educate healthcare staff about the correct use and limitations of the NEPTS service.

Providers should also re-examine the point at which mobility assessments are carried out. When hospitals carry out patient mobility assessments, this is often done at a fixed, predetermined point. If a patient is independently mobile, but has been sitting and waiting for a doctor’s assessment, the patient’s mobility levels could deteriorate. When crews arrive to pick up a patient that has been booked on a seated vehicle to accommodate four patients, the crews undertake what is called a dynamic mobility assessment of the patient. They then establish whether or not the patient can walk independently, and whether they might now require a wheelchair or stretcher. This means that the vehicle originally booked to transport the patient is no longer suitable, and more, or different, resources are required.

The reality is often different to the perceived activity levels within NEPTS, where the ideal scenario is multiple patients in the same mobility category travelling in one vehicle. If transport is planned at the last minute for patients with the lowest mobility (patients who need stretchers), this blocks out a significant number of vehicles in one go, thereby increasing delays and placing a greater strain on existing resources.

Of course, effectively balancing these factors comes down to proper planning, communication and funding contracts on actual resources needed, not just activity levels. This does not mean simply communicating with transport providers, but also between hospital departments.