Heatwaves are killing thousands every year – it will get worse

The damage of heatwaves to human health, productivity and lifestyles is growing. This is primarily because of the increasing likelihood of heatwaves caused by climate change. What are the impacts of this silent killer and what can be done about it?

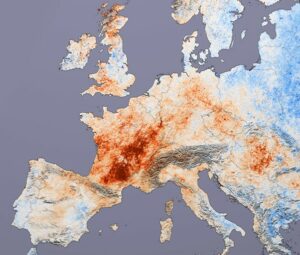

Seventy thousand people died during the 2003 heatwave in Europe – a fact that should pose frightening questions if scientific projections that suggest climate change will increase the frequency of heatwaves turn out to be correct. Yet, because the death toll and drastic impacts of heatwaves are not always so immediate and obvious, they rarely received adequate attention from policymakers and the public.

“When hot days come, people think it’s just time to go to the beach. They don’t think about the fact that heat can make people sick, it can kill them. Maybe it’s just human nature, but why doesn’t it spur public attention?” asks Kathy Baughman McLeod, founding member of the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance (EHRA) and SVP and Director of the Adrienne Arsht–Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center at the Atlantic Council. The EHRA, formed by more than 30 global organisations, seeks “to tackle the growing threat of extreme urban heat for vulnerable people worldwide”.

Of the impacts of climate change, heatwaves are considered to have one of the deadliest health impacts. According to The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change 2020 report, “from 2000 to 2018, heat-related mortality in people older than 65 years increased by 57 per cent and, in 2018, reached 296,000 deaths. The majority of these occurred in Japan, Eastern China, Northern India and Central Europe.”

What exactly defines a heatwave? Because they can vary significantly depending on a range of factors such as humidity, heatwaves do not have a universally accepted definition. One of the most common definitions that is attributed to them relates to an intensity that exceeds a certain threshold (there is no worldwide accepted threshold) and a duration that lasts a certain length of time.

How heatwaves impact human health, and who is most at risk?

Experts in the UK and US have concluded that extreme heat can cause a variety of negative health impacts depending on the intensity and duration of the heatwave. Some research shows direct correlations between increasing heat and an increasing number of excess deaths, which often double on particularly hot days. The main causes of illness or death during a heatwave are cardiovascular, respiratory disease and heatstroke.

Other heat-related illnesses:

- Heat exhaustion – the most common. It occurs as a result of water or sodium depletion, with no-specific features of malaise, vomiting and circulatory collapse, and is present when the core temperature is between 37°C and 40°C. Left untreated, it may evolve into heatstroke

- Heat cramps – caused by dehydration and loss of electrolytes, often following exercise

- Heat rash – small, red itchy papules

- Heat oedema – dizziness and fainting, due to vasodilation and retention of fluid

- Heatstroke – can become a point of no return whereby the body’s thermoregulation mechanism fails. This leads to a medical emergency, with symptoms of confusion; disorientation; convulsions; unconsciousness; hot dry skin; and core body temperature exceeding 40°C for between 45 minutes and eight hours. It can result in cell death, organ failure, brain damage or death

(Source: Heatwave Advice, Department of Health)

People most at risk are those over the age of 65, people with disabilities or pre-existing medical conditions and those working outdoors for long hours in non-cooled environments. Other factors that can increase risk include; limited access to green spaces, living in cities with high population density, living on a top floor and being homeless. Nowhere is immune to extreme heat but populations in the Europe and Eastern Mediterranean regions have been the most vulnerable of all the WHO regions, the 2020 Lancet report found.

People with chronic or severe illness are likely to be at particular risk, including the following conditions:

- Respiratory disease

- Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions

- Diabetes and obesity

- Severe mental illness

- Parkinson’s disease and difficulties with mobility

- Renal insufficiency

- Peripheral vascular conditions

- Alzheimer’s or related diseases

(Source: Heatwave Advice, Department of Health)

Other impacts of heatwaves

The impacts of heatwaves extend beyond people’s health; experts estimate that by 2030, lost productivity from heat stress at work, particularly in developing countries, will cost $4.2 trillion USD per year.

“Across the globe, a potential 302 billion work hours were lost in 2019, which is 103 billion hours more than were lost in 2000. Thirteen countries represented 80.7 per cent of the 302,4 billion global work hours lost in 2019,” The Lancet 2020 report found.

The 2003 heatwave was estimated to have cost £41 million in health-related costs and productivity losses in the UK alone. In the US, a 2014 study by economists Tatyana Deryugina and Solomon Hsiang looked at annual income data and daily weather data from 1969 to 2011 and found that years with more days above 59 F (15 C) are associated with significantly lower income per person: average per-day income declines by 1.5 per cent for each 1.8 F (1 C) increase in daily average temperature beyond 15 C (59 F).

Several studies have also found links between extremely hot days and the worsening of people’s mental health conditions. A study in Toronto associated the increased rates of emergency visits for mental health conditions to temperatures rising above 28 C (82 F).

Yet another equality issue

Like many public health issues, heatwaves do not impact everyone equally – they affect people of colour and lower socioeconomic status more than anybody else.

“The people contributing to it least are suffering the most. There’s a link between hot communities and trees. Low-income communities don’t have trees whereas suburbs do. Trees help keep the temperature down and, more importantly, they absorb pollution,” says Ms Baughman McLeod.

“By contrast, people of lower economic status and of colour are more likely to be living next to industrial complexes that are emitting pollution. Most of the time in those areas there are no trees that can absorb pollution and heat is a key component of that.”

This was confirmed by a 2018 paper in the US that found people living in less vegetated areas had a five per cent higher risk of death compared to those living in more vegetated areas. Scientists at the University of California in 2017 mapped racial divides in the US by proximity to trees. Results were clear: black people were 52 per cent more likely than white people to live in areas of unnatural “heat risk-related land cover,” while Asian people were 32 per cent more likely and Hispanics 21 per cent.

Heatwaves and climate change: a sign of what is to come

There are fingerprints of climate change all over the recent heatwaves. An overwhelming amount of scientific evidence suggests that climate change is already making heatwaves and extremely hot days more frequent and severe. The evidence also suggests that if immediate actions to reduce emissions are not taken, extreme weather events will become the norm. A 2019 report by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) found that the 2019 heatwave in western Europe “would have been extremely unlikely without climate change”.

More recently in 2020, Siberia hit a record-breaking temperature of 38 degrees celsius. Again, WWA found “with high confidence” that the January to June 2020 prolonged heat “was made at least 600 times more likely as a result of human-induced climate change.”

We must raise awareness

When Ms Baughman McLeod, along with international partners, decided to establish the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance in summer 2020, their first priority was clear: raising awareness among decision-makers. “We found that heat was the place where there was not enough attention. I think it’s ironic that in 60 or 70 years of climate discussions, and we call it global warming, we’re not talking about heat. It’s killing more people than any other impact of climate change,” she says.

A report published in 2021 by the WHO concluded that public awareness of the health risk is relatively high in places that are regularly affected by hot spells. However, it also found that “the risk perception of heat among healthcare providers may be significantly lower than it should be, given the objective risks faced by their patients.”

Worryingly, the report also revealed poor levels of awareness of heat warnings among health professionals, including nurses in care homes, as well as a lack of knowledge of existing heat–health plans among hospital front-line staff.

Heatwaves are a silent killer, how can you solve a problem people don’t know about? In a landscape of crises, if something is not burning, people are not going to address it.

– Kathy Baughman McLeod, SVP and Director of the Adrienne Arsht–Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center at the Atlantic Council.

How should we go about raising awareness and saving lives? The Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance believes that naming heatwaves can make a difference. Although Ms Baughman McLeod admits that this may not be as straightforward as naming hurricanes, she believes this can help save lives.

“We’re trying to build a framework that can be adapted at a local met service and the existing heat health warning systems,” she told Integrated Care Journal. “We’re piloting heatwave naming and we’ve put a science team together to help inform it. We’re also building a ‘how to name heatwaves policy’ toolkit for countries that we will take to the COP26 in Glasgow,” she adds.

It is now crystal clear that heatwaves are an international issue that is bound to worsen in the years ahead, causing tens of thousands of deaths. While heatwaves impact certain countries more than others, nowhere is immune. Policymakers and health professionals must close the current knowledge gap and put into place policies that safely protect the most vulnerable in our societies. As the chances of altering the global CO2 emissions fall year after year, more resources should also be dedicated to adaptation rather than mitigation.

It is now crystal clear that heatwaves are an international issue that is bound to worsen in the years ahead, causing tens of thousands of deaths. While heatwaves impact certain countries more than others, nowhere is immune. Policymakers and health professionals must close the current knowledge gap and put into place policies that safely protect the most vulnerable in our societies. As the chances of altering the global CO2 emissions fall year after year, more resources should also be dedicated to adaptation rather than mitigation.